Building trust to improve services

Leadership

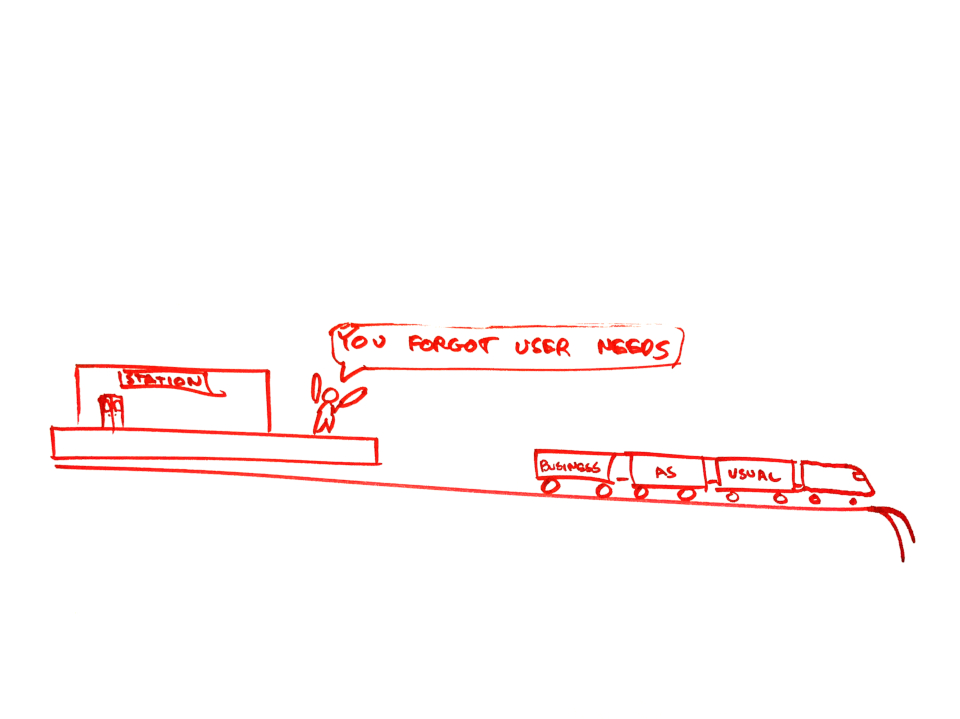

When the train has departed

In 2018, I sketched how my job makes me feel sometimes. It was at the International Design in Government Conference, in a session by Richard Hylerstedt to help people improve how they use sketching to communicate complex ideas in a simple way.

I was trying to capture that feeling of frustration when organisational inertia limits our ability to help teams to make decisions informed by user needs. The train has left the platform, and we're left shouting at the disappearing tail lights, asking ourselves why this happened. We know the train is heading to the wrong destination, and we keep thinking about how we could have caught it.

When we fail to influence people to make user-centred decisions, we're not doing a good job. To influence people to change their approach and actions, we need their trust, and we need to trust them. Trust helps us get on the business-as-usual train, and only then do we have the chance to change its direction to be more user-centred.

Designers need trust to affect change

Having the word "designer" in our job titles, at the moment, it means we don't usually have the power [1] or budget to have the final say on key product or business decisions. In the absence of this, we need ways of influencing the people that have power. Many designers are good at breaking down complexity, and communicating clearly. We can speak with all the clarity in the world, but if we don't have someone's trust, they won't be listening.

[1] I mean this in the sense of old power, decision-making responsibility and seniority. This is different from new power, gained from softer leadership skills, regardless of hierarchy.

Gaining trust in a hurry

For the past two years, our team at the Government Digital Service (GDS) has been advising teams of civil servants across government, with limited digital or design skills. As an internal Brexit consultancy, we help them better understand the impact of Brexit on their services, and what it means for users. Teams usually get referred to us by other parts of GDS. When the referrer feels they need help from a service designer, but the team don’t recognise this need, we need to gain their trust and convey what value our support will bring them.

We map out their services, we make some recommendations, and we help them through the next steps. It sounds simple enough, but this has been some of the most challenging work I've done. Through failure, I've learnt the importance of trust, and gaining it quickly.

Gaining trust quickly is something uniquely important for an internal Brexit consultant that doesn't have the weight of a big four day rate behind them. Big consultancies are able to create trust through charging high prices. When your advice costs a team nothing but the time it takes them to meet you, you have to find other ways to create trust. When that team's time is very limited, you need to be quick, or they will go their own way.

Recommendations with no weight

Nearly a year ago, I was asked to join a workshop at very short notice. A policy team needed help to figure out how to keep their service running after Brexit. That was my brief from the person making the referral. I had never met them before, and I didn't know what they wanted to get out of the workshop. I could see there were a couple of hours on the agenda for "service mapping", alongside day-long agenda items written in legalese I couldn't make sense of. I wasn't entirely sure what I was getting into.

At the time, I thought the workshop mostly went well. We got them to flex the agenda enough to go into more detailed service mapping so they could clearly understand the impact of Brexit on their users. Towards the end, after some quick prototyping, we agreed on a couple of different approaches to keeping their service running, which ought to be tested as part of an Alpha.

The team's digital capability was very basic, so we wrote down our recommendations, and how we got there, in as plain English as possible. We offered to meet them again, to go through it, and answer any questions. They replied saying they were going to follow the recommendations. We were able to step back because their own organisation's digital team were happy to take them through the next steps to procure a supplier to deliver the Alpha phase.

A few months later, I heard that they had ignored our recommendations, and got consultants in to implement an off the shelf customer relationship management (CRM) solution. Without testing prototypes before building a platform, this approach carried greater risk of the service being difficult to use, and more costly to run. I felt shocked, gutted and confused, all at once. I had people ignore recommendations before, but usually this comes with a "not now", or a "we're already doing this", or "we're taking forwards A, but not B or C" [2]. This time, they didn't even tell me.

From their perspective, they might have seen us as jean-wearing, "digital" people, gatecrashing their workshop, giving them the answers, without knowledge of the policy they knew inside and out. Suspicious.

[2] See also Janet Hughes - “The main stages of resistance to / adoption of new things”

Recommendations that carry

On a more recent support case, I noticed early on that the team were making some big assumptions, with little evidence of testing them in previous or planned work. The team wants to create a cross-government solution to identify businesses with a high degree of confidence, to combat fraud when government pays businesses.

When I first hinted that they were making some assumptions, it was swept aside. I was an untrusted outsider. I needed to present my feedback in a way that was at least unthreatening, but ideally seen as helpful to the team, not just me.

I managed to get a one to one with the sponsor, to understand their ambitions. We chatted over coffee. I was equipped with a document I had made of their assumptions, but I didn’t reveal it until I understood enough detail of what they wanted to achieve, and felt I had their trust. In patiently waiting, it meant I could highlight their assumptions, and contextualise how testing them would enable the team to reach their desired outcomes.

Compelled by this new perspective, the sponsor commissioned additional research with a different set of users. This led to a much stronger Discovery, allowing them to confidently pinpoint the biggest opportunities for improvement. Our work was commended by their Chief Digital Information Officer.

The missing ingredient

In the first case, supporting the policy team with Brexit, we didn't have their trust. The atmosphere in the workshop had been quite intense, but productive. We all wanted to have a clearer plan, given the fast approaching Brexit date. The “get sh*t done” environment didn’t lend itself well to openness or vulnerability. Without trust, people can’t be vulnerable, and without vulnerability, we take fewer risks [3].

We didn't have the time to understand their world, their problems and their objectives. Our recommendations might have been based on solid evidence, but we were challenging an approach they already felt was right. To receive critique well, and act on it, you need to trust the people giving the critique. You need to feel like they’ve got your best interests at heart. This can only come from a feeling of mutual understanding.

In the other case, supporting the business identity team, I waited until I had enough trust in me for my challenges to be listened to. My suggestions were framed as something that could better help them achieve their goals.

Reflecting on this story, and writing this blog post has been eye-opening for me. I’ve been seeking out more time with delivery managers, who are usually excellent facilitators, creating safe environments for openness, vulnerability and failure, which allow for creating shared understanding and building trust. If you are able to shadow a good facilitator, and ask them how they create these environments, I would highly recommend it.

Since then, I've been much more focused on understanding people, their objectives, and their fears. I'll turn down last minute workshops if I don't know what they want to get out of it. It means holding back from sharing your thoughts until you have enough context. Sometimes you have to let things slide in the moment, and wait for the right time to challenge someone. These small things can make a big improvement to how people react to feedback, which is crucial when we need to get more people focused on the needs of our users.

[3] I’m borrowing heavily from Sandra Kpodar, who wrote a great blog post about this.

How to build trust as a designer

Away from the extreme time pressures of Brexit, trust can be built more slowly with most people's immediate teams and stakeholders. However, there's something to be said for rapidly testing different ways to build trust, and creating feedback loops to help sense when you have it and when you don't.

When you meet new people you need to influence to improve services, keep asking yourself how well you understand their goals, their fears and their vulnerabilities. If the sequence of events doesn’t allow yourself to learn these things, get a coffee with them. It’s definitely harder if you aren’t in the same location. I’ve found that an initial face to face meeting is worthwhile, then once you’ve established trust, remote meetings work much better. I’d love to hear how others do this remotely, because I want to get better at that. Please get in touch on Twitter.

I've found that certain behaviours can help build trust as a designer. These behaviours are often associated with the newer, fuzzy interpretations of leadership. This is leadership as a set of soft skills that we can use to influence people in an organisation, in the long term and short term. Along with good communication, which many designers have already, you'll hear about behaviours like giving power away, active listening, empathy, inclusion, shielding etc.

For example, when you build an inclusive team, where everyone feels supported to speak their mind, you are also building trust in each other because you’ll have created an environment where people aren’t afraid to give and receive feedback. Trust is, therefore, an outcome of good leadership.

These are all really really valuable things to be doing, and these behaviours will ultimately help us build the trust we need to change and improve services.

Three tips for building and maintaining trust

To summarise, I feel these are the most important lessons I learnt:

-

Listen actively for signs of someone’s fears or vulnerabilities, and consider how your actions might impact them

-

Learn when to let things slide, and when to pounce

-

Show how your recommendations will help someone achieve their goals, as well as presenting evidence

So chase that trust, and we can steer the direction of more business-as-usual trains.

Next: 2020-W17 week note. First attempt at a week note

Previous: Sketches for scaling digital public sector procurement